Introduction

Why I stopped thinking of profiling as “pandas but automated”, and started thinking in Arrow batches and columns.

When I started working on dataprof, I thought I was building a fairly standard dataset profiler: scan a table, compute statistics per column, emit a report. It would be a CLI tool, with a Python API, something I could comfortably plug into data pipelines.

That plan lasted a few days.

Very quickly, Apache Arrow stopped being “just the in-memory format” and became the design center of the project. The moment I committed to Arrow arrays and RecordBatches, the profiler stopped looking like a glorified script and started behaving like a tiny analytical engine: columnar layout, batch-oriented processing, SQL via DataFusion, Parquet everywhere.

In this article I want to walk through that shift. We’ll start from what a profiler actually needs to do (beyond pretty HTML), then look at what changes when you put Arrow at the core, and finally see how this journey pushed me into contributing back to arrow-rs, especially around the Parquet reader.

The Problem a Data Profiler Really Solves

Before talking about formats and engines, it helps to reset expectations. “Profiling” can mean very different things depending on who you ask.

On the notebook side, profiling often means: point a tool at a DataFrame, get a rich HTML report, scroll through distributions and correlations, maybe save a PDF. It’s interactive, visual, and heavily tied to a single runtime (usually pandas in Python).

What I needed dataprof to do was different:

- Run as a CLI in CI/CD or data pipelines.

- Handle wide tables and large datasets, not just the 100 MB you can comfortably keep in RAM.

- Produce machine-consumable outputs, not only human-oriented reports.

- Integrate with both Rust and Python ecosystems without teaching each side a new bespoke format.

In other words, I wanted something closer to a system component than a notebook tool. And that requirement immediately raises a question: if profiling is going to sit in the middle of serious data flows, what’s the right internal representation so that I don’t regret my choice three months later?

Choosing Apache Arrow as the Core Abstraction

At that point, I could have done the obvious thing: operate on in-memory rows (structs, records) and only convert to whatever the caller needs at the edges.

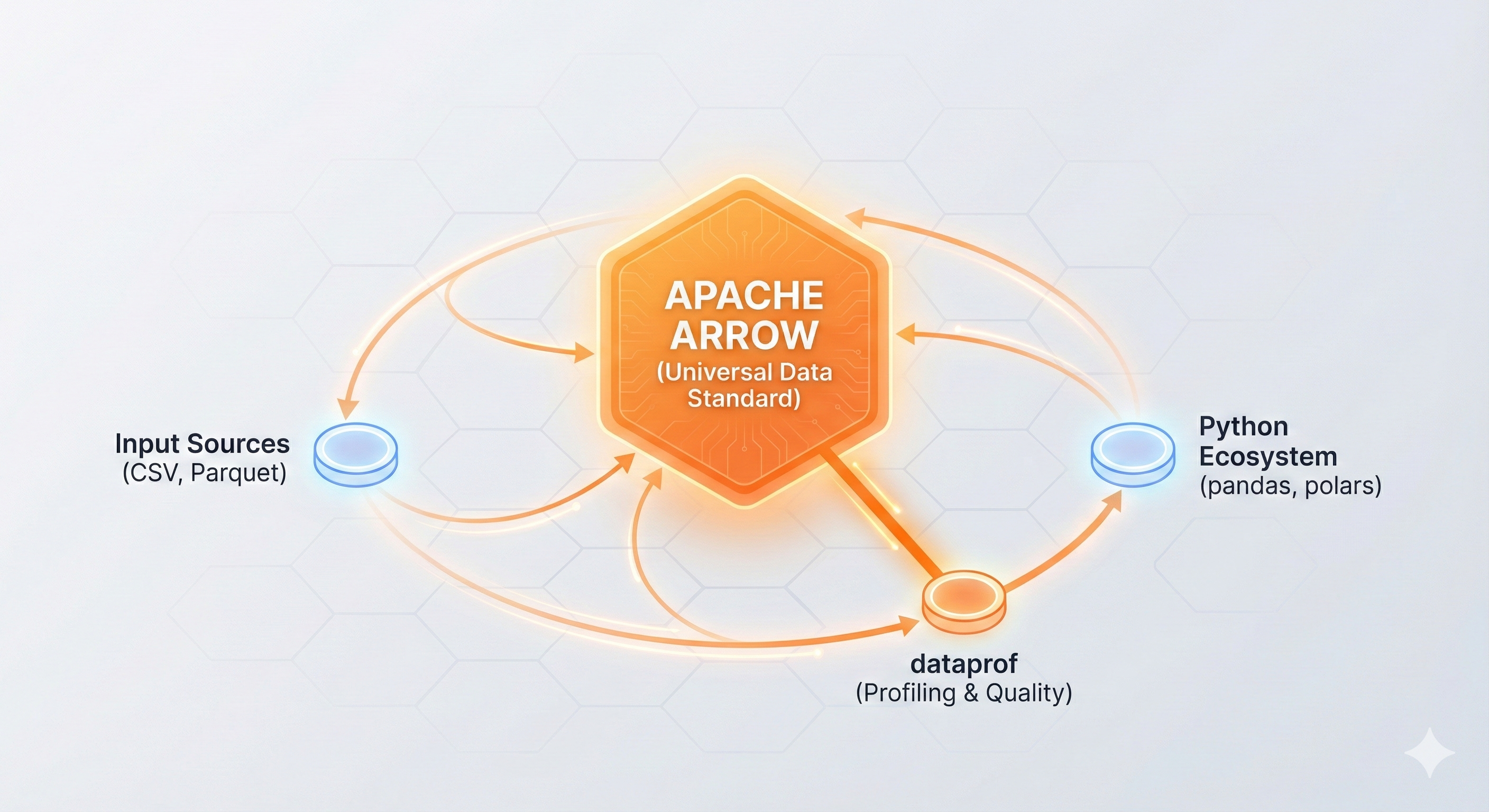

Instead, I chose to put Apache Arrow right at the center.

Arrow is a columnar, in-memory format designed for analytical workloads and zero-copy interop between languages. Once your data is in Arrow arrays and RecordBatches, you can feed it into Rust code, Python libraries, SQL engines like DataFusion, and formats like Parquet or IPC without a zoo of ad-hoc conversions.

That one decision had a few immediate consequences:

- I stopped thinking in terms of “rows coming from a file”, and started thinking in terms of batches of columns flowing through the profiler.

- The types in Arrow (

Int64Array,Float64Array,StringArray, and friends) became the contract between components rather than an implementation detail. - Interoperability with Python and Rust stopped being an afterthought and became a first-class goal: if I keep everything in Arrow, I can share memory instead of copying it.

In practice, Arrow turned out not to be a small implementation choice, but a constraint that shaped everything else.

From “files” to RecordBatches

One of the most important shifts was moving from “read a file” to “stream RecordBatches”.

A classic row-based profiler might read lines from a CSV file, parse them into some struct, and update counters as it goes. With Arrow, I wanted to operate on column chunks instead:

- The Parquet or CSV reader yields

RecordBatches of N rows. - Each batch contains a set of Arrow arrays, one per column.

- All metrics in dataprof are defined as operations on these arrays, not on arbitrary row structs.

This may sound like a subtle shift, but it changes the shape of your code. Instead of “for each row, inspect all columns”, you think “for each column chunk, compute statistics in a vectorized way”.

It also makes performance behavior easier to reason about: Arrow arrays are tightly packed, often SIMD-friendly, and align well with CPU caches.

Why Arrow instead of a custom format?

I could have designed my own columnar structs and serialization. But Arrow buys a few things I didn’t want to reinvent:

- A well-defined, language-agnostic memory layout.

- A Rust implementation (

arrow-rs) with reader/writer support for CSV, Parquet, IPC. - A Python story (pyarrow, pandas integration) that already works in many ecosystems.

- A query engine (DataFusion) that speaks Arrow natively.

For a profiler that aspires to sit in the middle of data flows, these are not minor perks. They are the difference between “this is my tool” and “this can become a piece of a larger platform”.

Design Notes from dataprof: Everything Is a Column

Once Arrow is in the middle, you start discovering which ideas survive and which don’t. dataprof forced me to crystallize a few design principles.

1. Every metric is a column operation

Profiling often boils down to answering questions like:

- How many nulls does this column have?

- How many distinct values?

- What is the distribution (histogram, quantiles)?

- How does this column behave across partitions or tables?

In dataprof, all of these are implemented as operations on Arrow arrays:

- Null counts become simple inspections of the bitmap and array length.

- Distinct counts use hash-based structures over array values.

- Histograms and quantiles are derived from the column values in batched form.

The key point is that the natural unit of work is the column, not the row. This matches Arrow’s design and makes it possible to vectorize operations, reuse code across backends, and reason about memory usage per column.

It also forces you to take Arrow types seriously. At some point, you stop thinking “string column” and start thinking “string arrays with potentially large, offset-encoded values”. Your profiler logic has to respect those semantics rather than flattening everything into generic strings.

2. DataFusion as a future SQL layer

One of the appealing aspects of designing around Arrow is that you get a SQL engine almost for free—at least in theory.

DataFusion is a Rust-native query engine that uses Apache Arrow as its core data model. If your profiler already represents results as Arrow RecordBatches, feeding them into DataFusion becomes straightforward.

This is a direction I’m exploring for dataprof:

- Materialize profiling results as Arrow batches.

- Register them as tables in a DataFusion context.

- Let users write SQL to slice and dice the results.

The architecture already supports this—dataprof’s internal representations are Arrow-native. The query interface isn’t fully built out yet, but when it is, Arrow is what will make it work with low friction: no impedance mismatch, no custom adapters.

3. Wide tables, many groups, and Parquet doing the heavy lifting

Not all tables are friendly. Some are very wide (hundreds of columns), others require profiling per tenant, per partition, or per other grouping.

These are the cases where naive implementations fall apart:

- You blow through memory by loading too many columns at once.

- You get killed by random access patterns.

- You re-implement optimizations that the Parquet reader already knows how to do.

Arrow and Parquet give you a different set of tools:

- Late materialization: only decode columns you need.

- Page pruning: let the reader skip entire chunks based on statistics.

- Batch size tuning: choose a batch size that balances throughput and memory for your environment.

In dataprof, I had to rethink some assumptions:

- Instead of “always read everything and compute everything”, I started to structure the profiler as a set of passes that can selectively touch columns.

- I leaned on the Parquet reader to minimize unnecessary reads, instead of writing my own indexing layer.

That experience ended up spilling back into arrow-rs itself.

From Code to Community: Contributing to arrow-rs

Working on dataprof pushed me deeper into the Arrow Rust implementation than I expected. In particular, I hit the limits of my understanding around the Parquet reader.

At some point, the only reasonable move was to fix things upstream.

PR #9116 – Preserving dictionary encoding in Parquet reads

One recurring scenario in profiling is categorical data: columns with many repeated values and relatively low cardinality. Parquet typically stores these with dictionary encoding to save space and I/O.

However, in practice, it was easy to end up with examples or code paths that eagerly decoded dictionaries into plain arrays, losing those benefits. For datasets with huge categorical columns, that can be both wasteful and slower.

In PR #9116, I added a new example to ArrowReaderOptions::with_schema demonstrating how to preserve dictionary encoding when reading Parquet string columns. The existing documentation showed schema mapping but didn’t cover the common case of keeping dictionaries intact.

This matters for tools like dataprof because:

- Keeping dictionary encoding can drastically reduce memory footprint when profiling wide, categorical-heavy tables.

- It keeps profiling closer to the “on-disk reality” of the data, which is useful when reasoning about layouts and performance.

What started as “why is this read so heavy?” turned into a contribution that helps anyone using arrow-rs for Parquet workloads, not just my own project.

PR #9163 – Making Parquet reader examples more self-contained

The second contribution came from a more human angle: many users (including me) were struggling with the “right” way to use the Parquet reader.

Real-world needs often look like:

- Read only a subset of columns.

- Handle fairly complex schemas without hand-rolling too much plumbing.

- Understand which knobs to turn when tuning performance.

In PR #9163, I updated three documentation examples in the Parquet reader to use in-memory buffers instead of temporary files. This makes the examples more self-contained and easier to follow in the rendered docs—small polish, but the kind that helps newcomers actually run the code.

Again, the origin was very local (“I just want dataprof to read Parquet in a sane way”), but the outcome is more general: the docs now make it easier to adopt the Parquet reader for serious workloads, including profiling tools.

Both PRs reinforced a lesson I first learned in the Tokio ecosystem: if you build around a powerful library, at some point your problems become indistinguishable from that library’s documentation gaps. Fixing those gaps upstream is both selfish and generous.

Shorter Bridges: Rust ↔ Python When Everything Speaks Arrow

One of the goals for dataprof was to be bi-lingual: a Rust crate, a CLI, and a Python package you can install from PyPI.

Choosing Arrow as the shared data model simplified that story enormously:

- The Rust core uses Arrow arrays and

RecordBatches as its primary types. - The CLI operates on Arrow-native inputs (e.g. Parquet) and emits Arrow-friendly outputs (e.g. Parquet/IPC).

- The Python package can expose results as pyarrow tables or pandas DataFrames with minimal copying.

That means I don’t need a custom serialization format between Rust and Python. The boundary is “just” Arrow.

This is very different from the naive approach of serializing everything to JSON, CSV, or some bespoke binary blobs. Those may work for small scripts, but they don’t scale well in complexity or interoperability.

In practice, Arrow gave me:

- A common contract between languages.

- A way to add new front-ends (e.g. a service exposing Arrow Flight or an HTTP API returning Arrow) without redesigning everything.

- The freedom to push more logic down into Rust while still making it pleasant to consume from Python.

When to Put Arrow at the Center (and When Not To)

After spending time living inside Arrow with dataprof and contributing back to arrow-rs, I have a more concrete sense of when this approach makes sense.

Arrow at the center makes sense if…

- You deal with medium to large datasets regularly, not just once in a while.

- You need to serve both Rust and Python (or other languages) without constantly reinventing interop.

- Your tool looks suspiciously like a mini analytics engine: you compute aggregates, filter, group, and want to reuse that logic in other contexts.

- You expect to interact with other Arrow-based systems: DataFusion, other query engines, data lake components.

In that world, the upfront cost of learning Arrow and its ecosystem pays off quickly.

…and when it’s probably overkill

On the other hand, I would think twice before centering everything on Arrow if:

- You are writing one-off scripts or small utilities where the main complexity is business logic, not data volume.

- Your team lives entirely in Python notebooks and has no appetite for Rust toolchains or columnar mental models.

- Your datasets are small enough that the bottleneck is your thinking time, not I/O or memory.

Arrow is a powerful abstraction, but it also imposes a way of thinking. If all you need is a quick “is this CSV broken?” script, a couple of pandas calls might be more than enough.

Closing Thoughts: Once You Go Columnar…

I started dataprof thinking in terms of “a profiler that happens to use Arrow”. Somewhere along the way, it quietly became “a columnar tool that happens to do profiling”.

Putting Apache Arrow at the center changed how I:

- Model metrics (columns first).

- Think about performance (batches, dictionary encoding, Parquet pages).

- Structure the project (Arrow in the core, DataFusion as a future query layer, shared types across Rust and Python).

It also changed my relationship with the ecosystem. The moment I hit the limits of the Parquet reader, the natural move wasn’t hacking around it forever, but opening PRs to arrow-rs to improve docs and examples.

Once you start thinking this way, it becomes very hard to go back to a world where every tool invents its own in-memory format and wire protocol. Columnar design stops being a performance trick and becomes a design philosophy.

dataprof is still a relatively small project, but it already benefits from standing on Arrow’s shoulders. And if there’s a meta-lesson in all of this, it’s probably this:

For some classes of tools, choosing the right abstraction early matters more than any individual optimization you’ll ever make.

Arrow, for dataprof, was that abstraction.